Money for Nothing

Carbon cartels and the rise of a phantom industry

Imagine you owned a few hundred acres of timberland

that you had no intention of cutting any time soon, but you get paid for

leaving the trees standing anyway because you sell “carbon sequestration”

as a new commodity.

Or imagine that you build a bunch of windmills. First you get subsidized

with federal tax credits, then you sell the electricity to a utility,

and finally you sell the “environmental amenities” of the

windmills (avoidance of carbon dioxide emissions) to a different buyer

as a completely separate revenue stream from the electrical output.

At first blush, it seems too good to be true. People can literally make

money out of thin air? Someone will actually pay you for a commodity called

“carbon offsets” that can’t be seen or measured and

gives the buyer nothing to show for in the way of ownership after making

the purchase? Who would do that, and why?

Carbon trading is now a $60 billion global industry, brought on by a

bizarre fear of a relatively harmless gas known as carbon dioxide (CO2).

Oregon has been a leader in the development of this esoteric concept,

and if Gov. Ted Kulongoski gets his way, virtually every Oregonian will

be part of the carbon market within a few years, whether they like it

or not.

At the moment, the carbon offsets market is mostly a voluntary one in

Oregon, with the exception of the electric utility industry. But the governor

wants to impose strict limits on CO2 emissions statewide, thus creating

market value for carbon offsets that would otherwise not exist. Whether

these offsets actually have any intrinsic value is a question every state

legislator should ask before voting to extend Oregon’s current carbon

rationing program.

Oregon’s 1997 Carbon Standard

In 1997 Oregon passed the nation’s first law regulating CO2 emissions

from new electrical generating facilities. The allowable emission rate

for CO2 from such facilities is 17 percent below the cleanest known plant

in the country. And the rate will be periodically adjusted to remain 17

percent below state-of-the-art. Therefore a power plant developer cannot

actually comply with the standard.

In order to get a permit from the Oregon Energy Facility Siting Council

(EFSC), the facility owner may choose to meet part or all of the reduction

target by making a one-time, lump sum payment of funds to the Oregon Climate

Trust, a nonprofit organization incorporated in 1997, to offset the carbon

emissions over the life of the power plant. In turn, the Trust must use

the funds to carry out projects that avoid, sequester or displace the

carbon dioxide that the plant will emit in excess of the required standard.

As an extortion scheme, this program has been tremendously effective;

all fossil-fueled Oregon power plants built since 1997 have made payments

to the Climate Trust. But once power plant developers hand over the protection

money, what do they get in return?

In its first 10 years of operation the Trust has spent more than $8.8

million on projects claimed to offset nearly 2.6 million metric tons of

carbon dioxide. One of the earliest projects it sponsored was an Internet-based

carpool program run by the city of Portland, called CarpoolMatchNW.org.

It was created in 2001 with $120,000 in seed money from the Climate Trust.

Portland’s Office of Transportation (POT) took the lead in implementing

the program, and other bureaucratic entities including Tri-Met, C-Tran

in Vancouver, and the city of Salem also signed on. The program was based

on the belief that if people could log on to an Internet site to find

compatible carpoolers, significant numbers of people would leave their

cars behind and begin ride-sharing, thereby avoiding the generation of

CO2, offsetting the emissions from the power plant that was forced to

pay the original $120,000 (as part of a much larger tab of $1.2 million

for other carbon emissions).

Project sponsors were very excited about the potential of CarpoolMatchNW.org.

Kris Nelson, then a program manager for the Climate Trust, told Michelle

Cole of the Oregonian in May 2001 that the Trust was enthused about the

program “not only for its potential to demonstrate real CO2 reduction.

But also because this starts to crack the transportation nut.”

It’s not clear what the transportation “nut” was, but

presumably it had something to do with the annoying tendency of motorists

to prefer private auto use over having to schedule car-sharing with others

ahead of time.

However, the project’s backers should have seen some large warning

signs right at the get-go. First, carpooling has been steadily dropping

over the past 20 years. To the extent that there is any carpooling at

all, it is dominated by so-called “fam-pools,” that is, family

members sharing rides, such as parents driving a few kids to school while

on the way to work. As Louise Tippens, the first manager of CarpoolMatchNW.org

noted at the time, “The interesting thing about Portland-area carpools

is that most are comprised of family members.”

Nonetheless, in a case of hope triumphing over experience, bureaucrats

charged forward into the Internet carpooling world. After one year of

promotion, the results were underwhelming. Portland had promised the Climate

Trust that carpooling would generate 2,000 tons of carbon offsets. The

estimated actual number was only 95 tons, or roughly 5 percent of the

goal. So few people signed up in the first year that a Portland Tribune

feature story on the program estimated each new carpool formed had cost

electricity ratepayers a whopping $29,000.

The program’s administrators were understandably upset with this

publicity and claimed it was too early to pass judgment. But the program’s

verification data showed motorists were not responding well to the campaign.

For the next three years, the targets jumped to 4,500, 7,500 and 8,000

tons respectively, but the cumulative offsets for the four-year period

only totaled 14 percent of the goal.

Local news media provided no coverage of this story, perhaps in part

because the project’s backers went out of their way to bury the

results. Each year, the Portland Office of Transportation is required

to submit a verification report to the Climate Trust. One would think

those reports would be available on the website of either the City of

Portland or the Oregon Climate Trust, or both. That assumption would be

wrong. Those reports are only available if specifically requested, and

apparently local news media never asked.

A breach of trust?

The Climate Trust now admits that the project failed. The Trust’s

website notes that the goal for the project was 70,000 tons of CO2 offsets

over 10 years, but it only achieved 3,075 after five years — and

those were estimated, not measured. Therefore, the Trust terminated its

contract with Portland in 2006.

A clause in the contract allowed Portland to fulfill its CO2 offsets

obligation by substituting offsets from other activities. After negotiations,

the city provided replacement offsets from two transportation projects:

the Eastside Hub project (20,614 metric tons) and the TravelSmart Interstate

project (4,268 metric tons). Both projects utilized “individualized

marketing strategies to reduce trips and promote alternative methods of

transportation.”

Oddly enough, despite five years of consistently disappointing results

from a project aimed at changing individual travel behaviors, the Climate

Trust accepted substitute offsets from two other projects designed, once

again, to change individual travel behaviors, without any attempt at verification.

According to Jed Jorgenson, who until recently was the marketing and communications

manager at the Trust, “While both are excellent projects, The Climate

Trust did not attempt to quantify their results. These replacement offsets

are not included in the Climate Trust’s offset portfolio.”

This is a clear violation of the Trust’s operating principles.

On its website, the Trust claims, “There are two key principles

the Climate Trust considers essential to the assurance of an offset’s

ability to deliver on its promise of an actual reduction in greenhouse

gas emissions: Additionality and Ongoing Monitoring and Verification.”

“Additionality?” The term means that the claimed offsets

result from activities or investments that would have not been made otherwise.

A commitment to “monitoring and verification” implies that

those forced to pay for offsets through the 1997 law actually get them.

The Trust states: “Each project must have a monitoring plan that

defines how, when and by whom the quantification will be done. All emissions

reductions must be verified by an independent third party.”

None of this was done for the CarpoolMatchNW.org project. The annual

reports to the Trust were submitted by the POT, not an independent third

party. The estimated emissions reductions were calculated based on surveys

of dubious quality, not actual observations of individual behavior. And

when the city finally admitted that the Internet carpooling program had

failed, the Climate Trust allowed them to backfill with a huge number

of offsets from two similar programs that the Trust admits it made no

effort to verify.

Even a cursory examination of the data related to the Eastside Hub project

and the TravelSmart Interstate project indicate that these projects suffered

from many of the same flaws as the Internet carpool program. The final

report published by POT shows that the Hub project was a labor-intensive

hand-holding exercise conducted from November 2004 to December 2005, in

which a small army of city bureaucrats attempted to persuade people in

certain Southeast Portland neighborhoods to get out of their cars. The

campaign included mass mailers, “Smart Living Classes,” and

a “Women on Bikes” campaign. They also gave away 390 bike

helmets to kids and parents. They spent more than $170,000 in materials,

required the use of 4.25 full-time equivalent staff positions for the

duration, and also received the support of three 32-hour-per-week staff

assistants for 12-14 weeks.

The combination of staff time and materials cost taxpayers at least $500,000.

Yet the report admits that compared with travel habits before the project

began, “carpooling remained the same” in Southeast Portland

at the end of the campaign.

The TravelSmart Interstate campaign was a similar marketing program done

in conjunction with the opening of the North Interstate light rail line.

Bureaucrats were hired, money was spent, brochures were distributed, and

in the end, little changed regarding travel patterns.

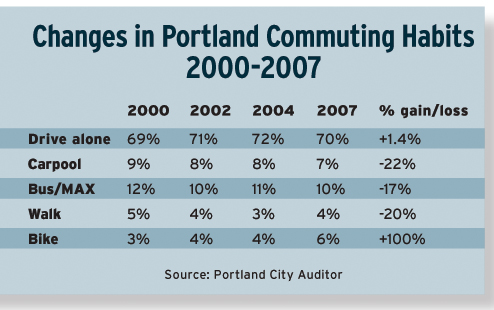

In fact, the Portland City Auditor publishes a “Services and Accomplishments”

report every year, which includes responses to telephone surveys. According

to the auditor, changes in Portland commuting patterns have actually gone

in the opposite direction of what local planners hoped for, despite billions

of dollars spent trying to get people to reduce their driving:

Solo driving has gone up, while transit use and carpooling have gone

down. This is especially remarkable given that three new light rail lines

have opened since 2001: the Red line to the airport, the Yellow line to

North Portland, and the extension of Red line service to Beaverton Transit

Center.

Accountability lapses

There appears to be little accountability in this process to ensure that

those who are forced to pay for carbon offsets get anything in return.

The City of Portland had a contractual obligation with the Climate Trust,

but the Trust allowed Portland to escape with non-verified replacement

offsets. The Climate Trust itself is obligated to submit a five-year report

to the EFSC, which it did in September 2004. But on page 10 of that report

it dedicates two short paragraphs of happy talk about the CarpoolMatchNW.org

project, claiming that it will offset 70,000 tons of CO2. Nowhere does

the report state that just three months earlier, POT had filed its annual

report with the Trust admitting that in the first two years of the project,

it had only secured 13 percent of its required carbon offsets. Clearly,

the carpooling project was not going to meet its goals, but that information

was withheld by the Climate Trust when it submitted its five-year report

to the EFSC.

When contacted in March 2008, EFSC Manager Tom Stoops professed to know

little about the carpooling program and its waste of Climate Trust funds,

even though the Siting Council holds three of the seven positions on the

Climate Trust’s board.

Meanwhile, the entity that was actually required to pay for the carpool

program — the Klamath Cogeneration Project, a 484-megawatt gas-fired,

combined-cycle power plant — did not receive any refund of the $120,000

paid to the Climate Trust.

According to Jeff Ball, city manager for Klamath Falls, the cogeneration

project (jointly developed by the city of Klamath Falls, Pacific Klamath

Energy and PPM Energy) was required to pay $1.2 million to the Climate

Trust, which the Trust then allocated to five offset projects. Once the

energy project developers cut the check, they had no voice in subsequent

decisions about where the money went. If the offsets never come to fruition,

they have no legal recourse, despite the fact that the state of Oregon

forced them to pay.

It’s also noteworthy that the 24,882 tons of offsets claimed by

Portland through the substitution process, if they actually exist, violate

the Trust’s “additionality” principle, because they

were undertaken for other reasons and with other funding. In other words,

they would have been achieved even if the Climate Trust had never been

incorporated. That may be why they are not included in the Trust’s

offset portfolio. But if that’s the case, then they aren’t

worth paying for, at least not by the Klamath Cogeneration Project.

On a final note, even with the replacement offsets, the total offsets

provided by the POT to the Climate Trust were 27,957. The contract called

for 30,000 in the first five years, but the Climate Trust signed off on

the lower number, apparently deciding that 93.19 percent of a contract

requirement was close enough for government work.

As for the CarpoolMatchNW.org program? Well, as is so often the case,

it was kicked upstairs where it can waste money on an even grander scale.

Effective July 2006, the program was transferred to Metro so it could

be implemented on a regional basis.

Mysterious offset money at Portland Audubon Society

The difficulty in trying to achieve real offsets through carpooling is

not an isolated case; virtually every carbon offset transaction poses

verification challenges. In 2005, one of the nation’s leading environmental

advocacy organizations, the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), claimed

in its federal tax filing to have purchased carbon offsets from the Portland

Audubon Society to “neutralize ED’s carbon emissions.”

This is supposedly important to EDF because the organization seeks to

stabilize global emissions of so-called “greenhouse gases”

and believes that this aim “can only be achieved with a worldwide

system that sets a limit on pollution, and employs emissions-trading to

meet that limit cost-effectively.”

Any group calling for mandatory carbon rationing has to “walk the

talk” by offsetting all its own carbon emissions voluntarily. According

to the organization’s federal tax filings, EDF claims to have done

this by paying Portland Audubon $16,500 for the offsets. This would not

be particularly noteworthy, except that EDF is headquartered in New York

City, and Audubon does not advertise itself as a seller of carbon offsets.

When asked about this, Meryl Redisch, the director of Portland Audubon

Society, was surprised that EDF listed the gift as an offset transaction.

According to Redisch, EDF contacted Audubon and gave them an unrestricted

gift of $16,500 for use by the Ocean Alliance. Audubon was sponsoring

the group at the time by serving as a fiscal agent for contributions.

The Ocean Alliance did not promote itself as a carbon offsets group, no

terms were agreed to with EDF, and no contract was signed. There were

no deliverables, and no efforts were made to provide EDF with carbon offsets.

The $16,500 was used by the Ocean Alliance for salaries of contract employees

and other general operating expenses.

The mission of the Ocean Alliance was to “advance ocean health

for biodiversity, thriving communities and our children’s future.”

This may be an admirable mission, but it has nothing to do with carbon

offsets.

As for EDF members who sent their annual donations to the organization’s

Park Avenue office in New York, only to have the money shipped out to

Portland Audubon Society on behalf of the Ocean Alliance for carbon offsets

never received? They’ll have to learn that when it comes to claims

of environmental advocacy, it is buyer beware.

Hot air in Europe

These are just a few small previews of coming attractions in the carbon

offsets world if Kulongoski persuades the legislature to adopt an Oregon

carbon limit in the 2009 legislative session. We already know that the

mandatory carbon market, which has been in existence in Europe since 2005

due to implementation of the Kyoto Protocol, has been rife with scams.

Russia in particular has gamed the system by successfully negotiating

carbon limits far above their actual emissions in 1990, the base year

for Kyoto compliance.

The New York Times wrote a feature story about the Russian energy giant

Gazprom in April 2007, noting that the company made a killing in carbon

credits for technology investments that it would probably have made anyway.

But those profits are purely an artifact of regulatory design. As the

Times put it, “At current prices, the total value for Russian carbon

credits could be between $40 billion to $60 billion. But if negotiations

to extend the Kyoto Protocols collapse, carbon credits could be worth

nothing.”

How could $60 billion of corporate assets become potentially worthless?

Because there is no underlying value to the carbon credits. Gazprom did

not actually create wealth for the world economy by developing new technologies

or improving labor productivity. They simply gamed a carbon cartel established

and enforced by the United Nations.

A lesson for Oregon legislators

The whole point of demonizing carbon, and then mandating limits, is to

create monetary value for carbon offset activities that otherwise would

not exist. That’s the lesson for Oregon legislators. If elected

officials accept the premise of climate alarmists that CO2 must be reduced,

the policy goal will be to create a massive run-up in the price of carbon

offsets by steadily ratcheting down the carbon limits. As the “bubble”

in carbon offset value rises, political pressure will grow to maintain

those high prices by limiting carbon-based energy even more, making it

impossible to undo the government-enforced energy rationing. This will

confer windfall profits on those firms who successfully manipulate the

system.

But consumers at large will have to pick up the tab – with almost

no offsetting benefits in terms of improved public health or a better

environment.

The reason there will be few measurable benefits is that CO2 is not actually

a pollutant. In roughly 38 years, the Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) has never regulated CO2 because exposure to it is not a health hazard,

and it does not harm plants or corrode buildings like other pollutants,

such as ground-level ozone. In fact, CO2 is an essential part of the globe’s

climate control system, without which Earth would be uninhabitable. Even

under eight years of leadership by the world’s most famous climate

alarmist, former Vice President Al Gore, EPA never regulated CO2.

The political campaign to demonize CO2 is based almost entirely on computer

animations of the future, usually in forecasts going out 100 years. Such

forecasts, trying to simulate the interactions of millions of poorly-understood

variables, have no policy value in the real world.

Despite his enthusiasm to begin rationing energy as a means of confronting

“global warming,” Gov. Kulongoski cannot even give a meaningful

definition of the term. Moreover, Kulongoski cannot show any evidence

that human activity in Oregon is affecting global climate, he doesn’t

know how much it will cost to reduce CO2 emissions, and he has no idea

if the social benefits (if there are any) will exceed the cost.

Neither the governor nor his top advisors have any idea if Oregon is

even a net emitter of CO2 or a net consumer, because no one has yet calculated

how much CO2 is taken up by the vast tracts of forest and farmland in

Oregon. Seeking CO2 regulation without knowing the amount of carbon sequestered

by plants is like an accounting firm declaring that a client has a financial

problem because they have expenses — without bothering to ask what

the revenues are.

Nonetheless, Kulongoski is determined to punish us for our energy use

by creating a carbon cartel, then offering a “market-based”

way of lowering the tariff by purchasing carbon offsets. This will be

a bonanza for the Oregon Climate Trust and the numerous other groups that

have already sprung up to take advantage of the regulatory feeding frenzy.

But for the average Oregonian, it will just be a hidden tax. There is

nothing market-based about it, because markets rely on voluntary transactions

where prices reflect perceptions of mutual gain.

The lesson here is an old one: Once money is taken from taxpayers through

regulation, there is no guarantee it will be spent wisely. In fact, most

of the revenue will likely be wasted on pork-barrel projects such as subsidies

to wind, solar and wave energy developers.

Squandered wealth

To the extent that this money, either tax incentives or regulated offsets,

is squandered on activities that the market would have voluntarily supported,

it is utterly wasted. To the extent that this money is squandered on activities

that the market would otherwise not support, carbon regulations will simply

destroy wealth while having no effect on the climate. Yet wealth creation

is the key to mitigating any impacts from global warming. Richer societies

are better able to anticipate change and invest in modern infrastructure.

Global warming alarmists in Oregon are already committed to mandatory

energy rationing as a statewide policy. It’s unlikely that mere

facts and evidence will dissuade them from the disastrous cap-and-trade

program they seek. The only way this will be halted is if average Oregonians

see it as the energy tax it is and demand that it be stopped.

John A. Charles Jr. is president and CEO of

Cascade Policy Institute, Oregon’s free-market think tank.

|