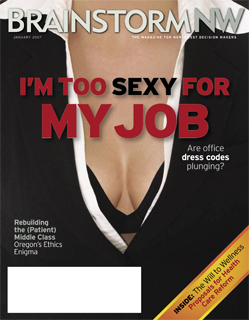

Are office dress codes plunging?

By Lisa Baker

Not long ago, Casual Friday was controversial.

A gift from the high-tech sector, khakis-and-Polos day hit a happy note with formerly buttoned-down office workers looking for a break from starched collars.

While many companies launched the one-day-a-week recess from formality, others protested, calling it sloppy and unprofessional.

There has been no shortage of debate about appropriate business wear in recent years. Portland police have waded into the issue of facial hair and tattoos. Even the NBA, in an effort to stifle comparisons between its players’ attire and gang member fashions, has introduced a dress code — of sorts — by insisting on tucked shirts, headgear, sunglasses indoors, and banning chains and medallions worn over clothing.

While there have been plenty of these kinds of discussions, the business world has been curiously silent about women’s work attire, preferring to simply direct its female employees to “dress appropriately and professionally.”

What they mean, corporate watchers say, is business professional, not street professional.

While most businesses won’t say it out loud, some women’s office apparel over the past five years has strayed beyond all “casual” definitions and slipped into something a little more uncomfortable for many in corporate life.

Skirts are shorter, necklines cut deeper, tops tighter, heels taller,

waist bands lower.

Lisa Kutcher, assistant professor at the University of Oregon’s Lundquist Business College and faculty advisor for the campus Women in Business Club, says young women graduating from college have spent little, if any, time in a corporate setting and have been taking their clothing cues on what to wear from the corporate America they see displayed on television and in magazines.

“When ‘The Apprentice’ came out, people thought, ‘Hey, I can wear that,’” Kutcher says. “But what we hear from businesses as a general consensus is that these styles are too revealing.”

In magazines, clothing ads for Banana Republic and J. Crew intended for the workplace are in Kutcher’s opinion “too tight, too revealing. A lot of clothing companies that have gotten into business clothes are places where we used to shop for going-out clothes. Fifteen years ago, if you wanted a suit, you went to department store where the clothes are more conservative.”

While young applicants might simply be making a rookie mistake, those more experienced in the work field are more likely making a statement with their attire, Kutcher says. “I think there are some who would say, ‘It’s okay to be a woman.’”

Nevertheless, she says recruiters visiting campuses have complained that applicants are pushing the boundaries and even crossing the line.

The uncertainty about what not to wear has prompted some businesses that had embraced casual wear in the workplace to button back down. “For instance,” Kutcher says, “a lot of accountants have gone back to traditional wear. Too many people were confused about what business casual was. Now they’re going back to what they know: the black suit.”

Janna Brown, a senior vice president of Portland’s Durham and Bates Insurance who’s worked at the company for more than 20 years, says she doesn’t see blatant cases of provocative dress in her industry. There is, however, what Brown calls “gaposis,” where a fitted blouse doesn’t actually fit, leaving a gap at the bust where the buttons are having a hard time doing their job.

She says women who dress provocatively will have a difficult time being taken seriously in the workplace — by men and women. “When you see that kind of thing, you think, ‘She’s here to get married. She’s here trolling, not looking to do a job.’”

Brown has a theory about why some women dress the way they do on the job. “It goes back to hunter-gatherer days when the men would go hunting and come back with a partridge and the women were hoping the hunter would pick them when he gets back, so they want to be noticed,” she says, laughing. “Even so, you’d think they would dress to their body types rather than just to the fashion. I don’t understand the great big butts in little pants. Seems to me when the hunter comes back, he says, ‘She go to end of line.’”

All joking aside, Brown says it used to be easier — for men and for women — to dress for success. “I think in the past there was an executive ‘uniform,’ whether it was a suit or something else that was career appropriate, and we learned from it who to have respect for. If someone is dressed casually, I’d think ‘sloppy dress, sloppy think.’”

Brown says she tells career women that they should be thinking about “the image you want to portray. In your mind’s eye, think about what you’re wearing. Even though you may look good in it, is it the image you want the other person to have if they have only 30 seconds to get an impression of you?”

And studies show, impressions mean a lot.

Researchers at Tulane University found that women who wear short skirts may be more likely to be passed over for promotions and pay increases.

A study publicized last year by USA Toda found that women who admitted wearing suggestive clothing to work or engaging in flirtatious behavior while on the job ended up earning less in salary — most fell in the $50,000-$75,000 range — than those who said they never did. The non-sexy workers earned between $75,000 to $100,000 per year, according to the research.

Kutcher says she hears much of the same thing from Oregon business people who make hiring and promotional decisions — they don’t take women seriously if they dress provocatively.

Barbara Baker, executive vice president of culture enhancement for Umpqua Bank, says the dress issue rarely comes up at the Roseburg-based bank, where most applicants know to wear conservative clothing to work.

“But when I worked in high tech, we sent people home for spaghetti straps, see-through fabric and cleavage. The problem is almost never in the interview, it’s the next day when they show up in skin-tight jeans,” Baker says. “No, I don’t care if they’re designer skin tight jeans.”

Umpqua prevents potential problems by providing its new employees with a wardrobe allowance that can be paid back from future earnings. “A young lady who just got out of school doesn’t have five nice outfits, so we give them up to $500 so they can start off with a wardrobe. We try to make it easy to dress appropriately.”

Personnel consultants say the business’ image is at stake, too.

A business advisor for AllBusiness.com puts it this way on the website: “What type of impression would your company give to customers should you have an employee at the front desk with a tongue ring and a T-shirt that says, ‘Who’s your daddy?’”

Judy Clark, spokeswoman for HR Answers in Tualatin, which counsels businesses on ways to prevent conflicts with employees over dress, recommends a dress code that “advances the image of the organization … It’s going to be different for each organization. A very hip, avant-garde business may allow very contemporary attire while those at a bank would not. To a degree, our attire, our business uniform, is our acting clothing. If it isn’t consistent with the job we do, credibility becomes a bigger hill to climb.”

Worse, she says, women who dress provocatively at work may unintentionally be “inviting people to nudge at the limits” of sexual harassment policy that could “migrate to something inappropriate or illegal.”

Victor Kisch, a partner and co-chairman of the labor and employment group at Stoel Rives LLP, says that although provocative clothing is not a green light to harass, he advises his corporate clients to adopt a dress code and counsel employees who violate it.

Kisch points out that sexual harassment is a consent issue and that inappropriate dress, coupled with flirtatious behavior, can be sending a signal that a co-worker’s attentions are welcome when they’re not. “You put that together and you make it more likely that you will be misinterpreted,” he says.

But confronting employees about dress issues can be dicey.

Brown says male supervisors and co-workers might feel that a woman in the office is dressed inappropriately but will not say anything for fear of being sued. “You won’t hear anything from guys. They’ve learned to keep their mouths shut. If they say something about it to anyone, it won’t be at the office.”

Kisch says supervisors whose job it is to correct clothing catastrophes are finding it complicated. “If your supervisor starts talking to you about your skirt, well, there’s a whole bunch of layers to that onion. The employee might feel it’s a personal attack. They think they look pretty darn good.”

While he encourages companies to find a female to counsel the worker, even that is “fraught with risk” because it often results in anger and morale problems.

Wendy Lane, founder of Lane PR in Portland, says the concept of professional

business wear has become an alien concept for many applicants. “Things

have absolutely changed over the years. There is very little sense of

professionalism. We’re in a field similar to accountants and lawyers.

It requires a conservative professional look. If someone comes to me not

understanding that in an interview situation, well, there are so many

(applicants) out there, it’s easy to say no.”

Brown says her industry, too, like many professional offices, is conservative. “We are beyond business casual. We are suits and ties. We aren’t trendy. Trendy is for hair dressers.”

Some corporate observers say the answer is to attack the problem while applicants are still in college or high school.

Lane does just that, speaking to business undergraduates about professional standards in attire and how it affects the level of respect a new applicant receives. “I think students are looking for direction,” Lane says. “They aren’t sarcastic or dissing it; they really want to know.”

Virginia Polytechnic Institute’s Career Center attempts to fill the void by publishing clothing guidelines for its students aiming to move into the business world. Among the tips is this one about skirts: “Showing a lot of thigh makes you look naive at best, foolish at worst. A skirt that ends at the knee when you’re standing looks chic and professional. Don’t purchase a skirt or decide on a hem length until you sit in the skirt facing a mirror. That’s what your interviewer will see.” About tops: “A fine gauge, good quality knit shell is appropriate underneath your suit jacket. Don’t show cleavage.”

The most succinct advice comes from Duke University: “Don’t confuse nightclub attire with business attire. If you would wear it to a club, you probably shouldn’t wear it in a business environment.”

Unless, of course, your business is actually a club.